What is Conflict in a Story and How to Write One in 8 Steps

Imagine you wake up, get dressed, make breakfast, and go to work without a single inconvenience. This scenario makes for a great stress-free morning, but not so much a gripping story to tell your coworkers. Now imagine you slipped on a banana peel and scratched your nose. Worse yet, you tore your expensive shirt. Now there’s a story to tell!

Very few stories can exist without some sort of problem. This is especially true for narratives written by authors and screenwriters because stories thrive mainly on conflict. So in order to write a great piece of fiction, you need to first know the answer to the following questions: what is conflict in a story, and how do I get it right?

Image by Freepik

In this article, we will give you a comprehensive guide to the meaning and applications of conflict in fiction. So let’s dive straight in!

In this article:

- Conflict in a Story Definition

- Role of Conflicts in Stories

- Types of Conflicts in Literature

- 8 Steps of Creating Conflict in a Story

- Practical Examples of Conflict in Stories

What Is Conflict in a Story?

Simply put, a conflict is the problem that characters face which forces them to take action in order to solve it. By taking this action, they actively affect the outcome of the problem and the direction that the story takes.

Some works of literature, such as novels, may have one major conflict that lasts from the beginning till the end. Others may have minor conflicts that can be resolved in as little as one or two chapters. Most stories have a blend of both.

While some genres can have big, life-or-death struggles, a conflict can also be as simple as forbidding a child from eating the cookies they want.

What Is the Role of Conflict in a Story?

When you inject conflict into a scene, you challenge your characters by forcing them to solve a problem. Most of the time, characters have to grow or change in order to be able to solve that problem.

Even the smallest of conflicts can have significant impacts on your story since a conflict can be any (or all) of the following:

- The main driving force for progressing the plot: Conflict is a vital component of storytelling. Without it, there is no substance to a tale. For instance, a fight that happens for no reason between the characters is not as meaningful as a fight over food or survival.

- A tool to explore themes or teach morals/lessons: If it’s relevant to your conflict, you can display themes like love, ambition, etc. through the lens of your story. Moreover, exposing your characters to situations that challenge their beliefs or lives offers a powerful opportunity for them to learn profound lessons. In fact, even fluffy slice-of-life stories can utilize minor conflicts to inject deeper meaning into their scenes.

- A major source of entertainment for your audience: People love drama, and the best way to deliver it in your story is by adding conflict. By integrating conflict skillfully into your story, you create a thrilling and emotionally engaging experience for your readers.

What Are the Four Types of Conflict in Literature?

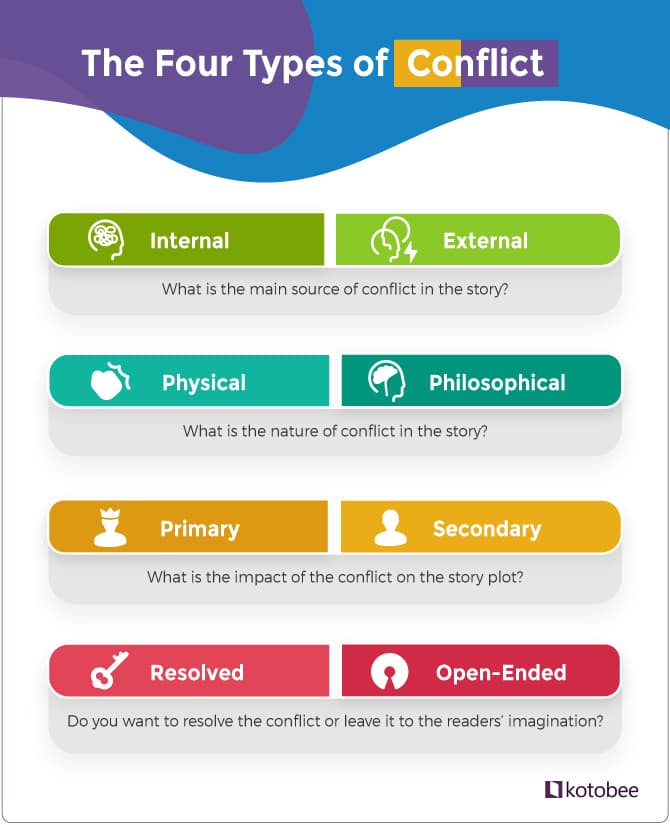

The type of conflict you will be using in your writing will rely on your genre, your character archetypes (or lack thereof), the tone and setting of the story, and the medium you are writing in (novel, screenplay, comic, etc.). One more thing to note is that it’s common practice to combine types of conflict because it serves to flesh out your story!

Even though it’s hard to sort conflict into types, there are some common categories that describe different aspects and dynamics of a conflict. These categories help us understand the nature of conflicts by providing a framework for analyzing and addressing them. Below are some of the most common categories of conflicts.

1. Internal vs. External

We can categorize conflict based on the source of the problem into two types: internal and external. From the wording, you can guess that internal conflict happens inside a character’s mind, while external conflict is forced on them by a third party. We can highlight the differences between the two types as follows:

- Internal conflict centers on the character’s internal struggles against their beliefs, morals, wants, and/or needs. This conflict can be a question of emotion, philosophy, or logic. Examples include choosing a worldview, adopting a steadfast belief in an unstable environment, and embracing or rejecting their feelings.

- External conflict comes from any outside force that doesn’t directly relate to a character’s psychology. It can be caused by an event, a person, or even the forces of nature. You can think of a work demotion, a villain terrorizing the city, or natural disasters like hurricanes and earthquakes.

2. Physical vs. Philosophical

In the realm of storytelling, conflict can appear in a physical form, like people or objects hindering the hero’s path, or in an abstract form, like religious conflict or mental illness. Both types tell us the nature of the conflict and how it affects the story and/or the characters.

With physical conflict, you have concrete obstacles in your characters’ paths. For example, villains, doomsday devices, and even opinionated family members are sources of physical conflict. Meanwhile, philosophical or moral conflict threatens their abstract beliefs, emotions, and/or state of mind. Non-physical dilemmas such as choosing between feeding an orphan or your own children is an example of a philosophical conflict.

3. Primary vs. Secondary

Also known as the main vs. side plot, a struggle becomes a primary or secondary conflict according to its impact on the characters and the plot. The table below summarizes the differences between these two types:

| Primary Conflict | Secondary Conflict | |

| Definition | The biggest (overarching) struggles that become the main focus of the story | Smaller, less impactful conflicts that are usually resolved much more quickly |

| Duration | At least a few chapters up to an entire series | A few chapters but not more than half the story |

| Purpose | Moves the whole story forward | Adds depth to the characters, sets up new plot events, or purely for entertainment/reducing tension |

| Number per story | 1 or 2 at most | Can be 3 or 4 |

4. Resolved vs. Open-Ended

One final decision to make is whether or not you want to resolve the conflict of your story. This is not a type of conflict as much as it is a choice you make when crafting your plot. Leaving the ending up for interpretation might enrich your conflicts if your main plotline relies on abstract concepts or ideas. Meanwhile, resolving conflicts leaves your audience satisfied with knowing the ending of your story.

Making this decision will rely to a great extent on the genre that you’re writing your book in. If you are writing a cozy mystery, for example, it’s common to settle your main conflict and solve the mystery. This helps bring closure to the narrative and offers readers the gratification of seeing the detective’s efforts come to fruition. However, many genres—like horror—can benefit from an open-ended resolution to a story’s climax. This serves to keep the audience guessing about the characters’ fates. If the story is interesting enough, they might even create their own theories for how the story will unfold.

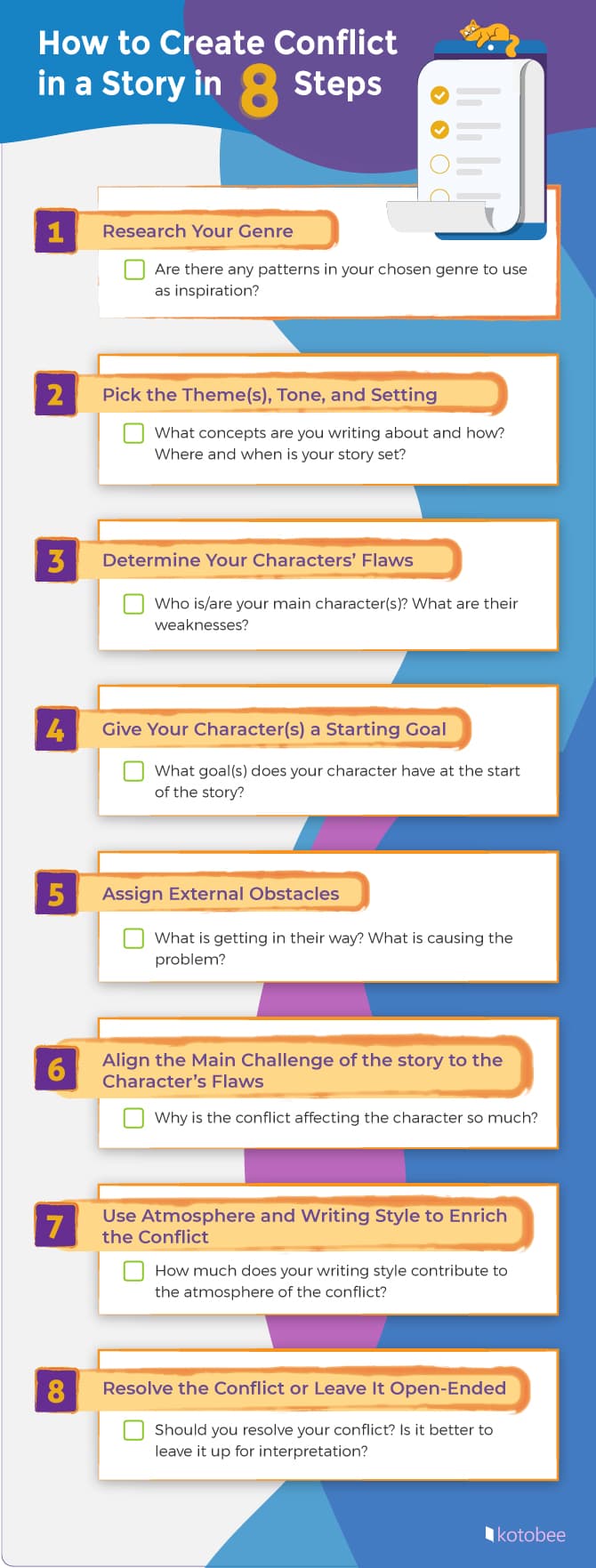

How to Create Conflict in a Story in 8 Steps

Now that you know the definition of conflict in a story, we can move on to creating one. But creating conflict isn’t always easy. It takes careful planning and execution to make your conflict believable, effective, and tailored to your characters. Additionally, your writing style must fit the genre you choose.

Here is a robust guide to creating good conflict in your story:

1. Researching Your Genre

The first step in creating a believable conflict is to check out existing works in your genre. No two books are the same, of course, but there might be some broad patterns and trends to note down for inspiration.

For example, mystery books tend to have suspenseful conflict and lots of tension. Alternatively, fantasy stories usually have complex world-building, so the conflict can come from, say, fictional politics or ancient prophecies.

2. Picking the Theme(s), Tone, and Setting

A light-hearted comedy will have a completely different conflict from a dark, gritty tragedy. Just like your genre, the themes, setting, and tone of your story will greatly impact how you outline your conflict. Let’s talk about why below:

- Themes: Themes are abstract concepts that the writer wants to communicate through their story. They can lead to conflict in ideas, philosophies, actions, etc. Themes like familial love and ambition, for example, might lead to conflicts such as a struggle for power overruling a kingdom.

- Tone: The tone of a story is determined by your own attitude and perspective on the themes you are writing about. You can be sympathetic to a cause, critical, judgemental, ironic, and so on. Since your attitude shapes your writing style, your writing will convey a particular mood or message on its own.

- Setting: The setting is the physical place and time period in which the events of your story are occurring. You can have several settings if you wish, but make sure to properly establish each of them so you don’t confuse your audience. By choosing a particular setting, you are also defining the nature of your conflict and its implications on your characters. For example, a modern-day working woman will have completely different experiences and challenges from a poor maiden in the Medieval period.

- Mood: The story’s mood is the general atmosphere and feelings that the setting conveys. Determining the mood of your story will influence how light or dark your conflict and writing will be. For example, a Victorian-era manor may give off a romantic but gloomy mood, which can set the tone for a melancholic romance that ends in tragedy.

- Point of view: Another point you want to think about is choosing the point of view of your story. Generally, the first-person point of view helps your audience connect to the narrator (usually the protagonist) of the story. The third-person point of view, on the other hand, is better suited for following the plot.

You can use the first person for various reasons, among which is making your protagonist’s suffering more relatable for the audience. Alternatively, using the third person places some distance between the audience and the story, which allows you to focus on more than just one character or setting.

3. Determining Character Flaws

Since the conflict has to challenge your characters in some way, you have to know your characters’ strengths and weaknesses. As a result, determining their flaws is a very important step because the conflict they will face must challenge those flaws. So, the question now is, how do you design flaws for a character?

When writers reach this part in the outlining process, they make a common mistake: writing quirks as flaws. As you will see below, there is a huge difference between the two:

- Flaws are fundamental aspects of your characters’ personalities that can have a negative impact on themselves or their surroundings. These can include narcissism, greed, anger management issues, and insecurities. These flaws are essential to building a complex and believable character, so they often become the target of a conflict.

- Quirks are unusual or strange things your characters may say, do, or think about differently from others. For instance, they may eat ice cream with a fork, have a catchphrase, or refer to themselves using the third person. Quirks can be positive, negative, or neutral, but they are shallow representations of your character’s behavior and don’t say much about character depth on their own.

A good story will have a good mix of flaws and quirks, as quirks are the icing on the cake that truly brings a character to life and can make them more memorable. However, the conflict must challenge flaws rather than quirks in order for the story to have high stakes. A character with many quirks but no real flaws does not contribute to the stakes of the plot.

4. Giving Your Character(s) an Initial Goal

Now that you have your main character(s) figured out, now is the time to give them a goal they want to achieve at the start of the story. For instance, your character might want to start over in a different career before she finds out that she’s having a baby (conflict). Here, the initial goal is the desire to switch careers, which may or may not change because a conflict is challenging it.

Sometimes the initial desires your character has will stay the same, but sometimes the character will adjust or even completely change them because of the conflict they are facing. By adapting this idea to your story, you are making your character more believable and raising the stakes of your conflict at the same time.

5. Assigning External Obstacles

An obstacle is a physical or non-physical object that stands in the way of characters solving a problem or achieving a goal. Obstacles are perhaps the most well-known element of a good story conflict because they are usually obvious and tend to directly affect characters’ lives.

Naturally, there is a broad range of creative potential that even experienced writers may underestimate when designing obstacles in their characters’ paths. One good example is using simple inconveniences as powerful catalysts for a greater conflict. For instance, your main character might run out of milk and get kidnapped on their way to the store. In that example, the obstacle was running out of milk, and the conflict was getting kidnapped.

This step goes hand-in-hand with your character’s starter goal and the main conflict they will face. If the obstacle makes your characters pause to think of a solution, it counts as an obstacle that causes conflict.

6. Aligning the Main Challenge to Character(s)’ Flaws

If there is any growth for your characters to achieve, it can often happen when their flaws are challenged in an unavoidable way that forces them to think or act differently. More importantly, the conflict must relate to your character profile; if your character has insecurities about their appearance, for example, the conflict can come from participating in beauty contests or having a cruel parent who is obsessed with vanity.

When matching conflicts with character flaws, you have a number of routes you can take. Most authors like to change some aspects of their main characters’ personalities over time, but this is not a strict requirement for resolving story conflict. Some authors use what is known as a “flat character arc”—where the main character does not change fundamentally, but they do create such changes in the people around them. But even then, the conflict still has to challenge the characters in a way that impacts them and their environment.

7. Using Atmosphere and Writing Style to Liven Up Conflict

Now that you have your main conflict outlined, why not add some flair to it? The most common piece of writing advice of “show, don’t tell” applies best here. This is where you take advantage of language, style, and character dialogue to fully immerse your audience in the story. Your ultimate goal is to transport readers to your fictional world, making them feel as if they’re experiencing the characters’ struggles and triumphs firsthand.

Here’s how you can use atmosphere and writing style to enrich conflict as you write your story:

- Atmosphere: As you’re writing your story, you are also creating an atmosphere that fits the conflict, be it dull or somber, full of intense action, or comedic and light-hearted. You can do this by describing the areas your characters visit, the weather, and other aspects of the setting. Another way to establish atmosphere is to have character dialogue that reflects their environment and setting. For instance, you can set up a dark, scary atmosphere by using stormy weather, an abandoned cemetery, and whispered dialogue.

- Writing style: Using certain words and phrases can turn a bland argument into a showdown, witty banter, or funny dialogue. Short sentences and simple words add more punch to your writing, while longer sentences and poetic vocabulary can paint pretty pictures in your audience’s minds. As such, your writing style will greatly influence how your audience feels about the events of the conflict.

8. Resolving Conflict vs. Leaving It Open-Ended

Most stories include resolutions to their main conflict. It is the best way to bring relief to your characters and your audience after a long struggle. And yet, many writers take the risk of leaving conflict unresolved or open to interpretation.

There is no clear answer or method of instruction for resolving conflict. With that said, you might see some genres leaning towards one or the other due to their unique traits. For example:

- Cozy mysteries, high fantasy, and other genres that require detailed worldbuilding might favor resolving the main conflict. The more elaborate the world and its story, the more likely that multiple loose ends will remain after the story’s climax. Leaving too many of those loose ends unresolved might leave many readers dissatisfied with how you ended the story.

- Literary fiction, slice-of-life stories, horror, and other genres that rely less on worldbuilding might work well with an unresolved ending. Since these genres tend to have introspective writing styles, the conflict can then be abstract enough that it makes more sense to leave the ending open to interpretation.

That is not to say that fantasy stories must have satisfying endings, or that you cannot resolve conflicts in literary fiction. At the end of the day, whether or not you settle your conflict will rely on every part of your story and your outlook on its themes.

Need to print out this checklist? Download it here!

Examples of Conflict in a Story

Now that we are aware of the different types of conflict in literature and how to create one, let’s explore how this knowledge can apply to real-world media. Here are some examples of popular stories making use of conflict and what you can learn from them in practice.

1. Short Stories/Novellas

Short stories and novellas usually limit conflict to one main struggle and maybe another minor one that is resolved quickly or does not affect the main plot. Let’s take A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens as an example of a novella.

- Overview: The main character, a gnarly, bitter old man named Scrooge, hates Christmas and mocks any who celebrate it. However, the ghost of his late business partner, Marley, visits him on Christmas Eve and explains how his greed and selfishness have led to an endless existence as a chained spirit. After each Christmas spirit takes him on a journey, Scrooge realizes that his perspective of life is very different from reality.

- Conflict analysis: Scrooge is a lonely man who lives in fear of unpredictable human interaction. However, the other characters thrive on it and live happily, believing that the best way to live is to share your life with others. In the end, Scrooge’s journey motivates him to make a conscious effort to honor Christmas and share his wealth with those who truly need it.

- Types of conflict: The novella’s main conflict is split into two categories: internal and external. Scrooge’s external struggles with Christmas celebrations and the visions that the spirits show him reflect his internal conflict and his twisted, fear-fueled outlook on life.

What makes this story truly successful is how well the conflict aligns with Scrooge’s character and his flaws. Whether it’s internal or external, Scrooge suffers through many world-shattering realizations that force him to reevaluate his outlook on life and thus grow as a character.

2. Novels

Novels have the privilege of being lengthy, which helps authors explore conflict and characters in more detail. Since the minimum length of a novel is fifty thousand words, it’s much easier to flesh out conflict and expand character arcs. We will take a deeper look at conflict in novels by examining Six of Crows by Leigh Bardugo.

- Overview: Throughout the novel, a group of misfits and thieves called the Dregs band together to perform an impossible heist by breaking into a foreign fortress. Along the way, they face external conflict in the form of physical enemies, like the soldiers of the fortress and the merchant who hired them. They also face an internal conflict between their innermost desires for love and redemption and the beliefs they’ve adopted as they struggle to get by.

- Conflict analysis: At the end of the novel, each character has undergone some form of growth. While it doesn’t change their grey morals, this maturity does give them the incentive to take down the corrupt merchant and save their captured friend, Inej. Kaz Brekker, the protagonist, appears to have been the most changed, going as far as to strike a deal with his arch-nemesis, Pekka Rollins, in order to save Inej.

- Types of conflict: There are several types of conflict present in the novel. While the whole gang shares a common goal of obtaining money, each individual has their own thoughts and beliefs that clash with their true desires. This inner clash generates a significant degree of internal conflict among them. For example, Kaz’s harsh upbringing has made him emotionally distant and unable to cope with his feelings for Inej. Plus, infiltrating an enemy fortress is a good example of physical external conflict.

3. Screenplays/Movies

Conflicts with more structure shine best in screenplays as most of them are segmented into three acts, each with its own side conflict. Most screenwriters will structure their main and side conflicts very clearly so that the script translates well on the screen. Let’s take a look at the first Hunger Games movie to see an example of a screenplay conflict in action.

- Overview: The protagonist, Katniss Everdeen, volunteers in her sister’s place to join a barbaric televised competition in which teenagers, adults, or even children fight each other to survive. While fending off other contestants, she toils in the dangerous arena to defend herself from natural hazards like predatory animals as well as search for food and water.

- Conflict analysis: Katniss faces conflict every step of the way, from her fear of violence to physical fights against kids from other districts. She must also try to survive without compromising her morals. By the final arc of the movie, she does win the competition alongside another contestant from her district, but at the cost of making up a love story to win TV viewers’ sympathy.

- Types of conflict: Throughout the movie, you see external conflict in the characters fighting for their lives (character vs character) and a dystopian governing system (character vs society). Even if Katniss’s main focus is on staying alive during the Hunger Games, she is also fighting for freedom and rebelling against the dictatorship of her nation. Plus, she is internally torn between her hatred for violence and her will to survive against all odds.

4. In Comics

Finally, comics strike the middle ground between novels and screenplays when it comes to conflict; they usually follow structural plot arcs like the Three-Act model, but these arcs can vary in length from a few pages to several volumes. Additionally, conflicts in comics can rely on images and also on dialogue, just like scripts. They can also appear in world-building texts or explanations that are usually written in the form of footnotes. To illustrate those points, we will look at the plot of Death Note, a Japanese manga by Tsugumi Ohba and Takeshi Obata.

- Overview: A genius high school student named Light Yagami finds a strange notebook called the Death Note. By writing a person’s name in it while imagining their face, Light can kill anyone he pleases. This plants the idea of a savior complex in his mind as he strives to rid the world of criminals and create a utopia in which he will rule supreme. When the authorities catch onto Light’s actions, the world’s greatest detective, a mysterious man who goes by L, demands to work the case alongside the National Police Agency in Japan. He becomes the biggest antagonist to Light’s quest, and the duo starts to run in circles around one another, each trying and failing to uncover the other’s identity.

- Conflict analysis: While the manga does have a very clear philosophical conflict between Light and L, the main emphasis is on the physical conflict between the two as they each try to catch the other. However, both of them do experience internal conflict throughout the manga.

- Conflict types: In terms of internal conflict, Light initially doubts himself and his actions because those actions contradict traditional ideals of human life. On the other hand, the more involved L gets with the case and with Light, the more conflicted he feels. He struggles to balance his duty as a law-abiding detective with his own morals and beliefs about justice.

Final Thoughts

Conflict is a vital part of any story, and it is important to carefully align your character’s traits with the struggles they will face. With that said, if you’re a writer who has a hard time brainstorming conflicts, then you can use the tips in this article to make the process easier for yourself. Writing conflict can be a loaded task, but it can also be fun!

.

Read More

Keeping the Suspense Alive: 5 Tips to Write a Perfect Cliffhanger

How to Write a Compelling Story Outline: A Step-by-Step Guide

Elements of Fiction: A Quick Guide to Writing the Perfect Story